Book Review: A State of Struggle. John McInally.

- msmithorganiser

- Nov 17, 2025

- 6 min read

Powerful corrupting forces swirl and surround unions. They act equally on both the “permanently organised faction” of full time officers set to manage the union and the elected lay representatives set to govern it.

This corrupting influence can take many forms apart from just the obvious cash bribes and watches as gifts from employers, pay talks in exotic locations etc… all designed to bend the union agenda but which remain rare and easy to spot.

But other forms of corruption often hide in plain sight, including the industrial and political forms where the strategic goals of industry, Political parties or the establishment are put before the goals of the union members in dispute quite openly, via pay review bodies, a focus on parliamentary process and concessions in the name of "partnership"

And all this can be intersected by a sort of relational corruption where networks based on faction, cronyism and nepotism operate on decision making in unions to put their networks needs first. Often acting with MAGA style protection rackets for the guilty and Labour style weaponised investigations of any of the innocent who can be denounced as “trots” .

My direct experience of taking on these corrupting forces will be discussed in more detail in forthcoming blogs. For now this latest contribution to the debate over union building in a modern setting by my friend, comrade and mentor John McInally picks its way through the internal realities faced by those driving change in Public and Commercial Services Union (PCS) against the headwinds of corrupting forces.

With recent revelations from the Blacklist Support Group, and the Spy Cops Campaign concerning police and security service involvement in our unions, it would be naïve in the extreme to presume that these forces were indifferent to who ran the civil service unions 40 years ago – and acted to influence events.

Although major unions representing staff in defence related industry and industries critical to Britains infrastructure, have had their fair share of state intervention and interest, in this respect the degree of meddling within PCS is likely to be unique and this thread is well developed in the narrative

So, so what? Some will argue that the combination of headwinds facing leaders of the PCS union since the early 1980s, (which Johns analysis presents an excellent narrative study of), are so unique as to offer no general lessons to be learned in other organisations. Certainly PCS and its founding unions has had a scale of factional organising across the whole political spectrum (including Conservative Party activists) rarely seen in any other union. This culture both stems from and supported the growth of a deep culture of lay member democracy and on the job training for local reps that should be the envy of other unions – despite its attendant challenges.

The scale. not the substance is what makes the PCS context unique.

There is plenty of detail in the book for students of PCS factional politics to enjoy, be reminded of, (in my case for sure), and discuss.

But at root, the book explores the tensions between the two broad approaches to union building that have been common across our entire history but have become in growing conflict over the previous 50 years as the “post war settlement” decayed and disappeared. These separate approaches appear in one form or another in most if not all unions, whether acknowledged, openly visible, or not. And even in unions with no organised left and right factions. Or just secret ones.

Many attempts are made in unions to harness together the two approaches to union building that provide the background to the narrative in this book to keep a temporary kind of “entente cordiale” going. But in the end the models are in competition, conflict and contradiction to each other on a philosophical – and political - basis.

And this conflict of ideas lies at the root of what this Organising for a Change blog spot and podcast are about, and the entirety of my time as an organiser and organiser leaders across half a dozen union bodies.

Left and right strands exist across all unions in my experience – but mostly exist in relation to each other in each union more than in relation to an immutable set of ideas and philosophies. The ”left” philosophy of union building that I belong to does not necessarily translate into the existence of a formal union left faction – but every left union leader I have met broadly pursues this approach.

At root our philosophy of union building promotes an ultra democratic approach. Bargaining and building rooted in the kind of deeper cultural ideas reflected as an example in the “ubuntu” culture centred by trade union and social movements in Central Africa. Summarised as – “I am. Only because we are, We are. Only because I am”.

The alternative and previously dominant British union philosophy raises autocratic policing of members and disputes by union officials, paid or elected, over mobilising union members support. Pursuing elusive partnerships with employers as opposed to building growth in our own power, chasing conflict resolution by “expert negotiators” over grass roots union campaigning.

Promoting “best that could be achieved bargaining” promoting despair and defeat in dispute. Often creating a circumstance where the first time union members are told that two strangers discussed their pay in London, is when they get told to vote for the outcome as the “best that could be achieved through negotiation” – or vote to strike if they dont like it.

Falling into the “dented shield” approach of concession bargaining in the hope someone or something, somewhere, will solve our problems for us. Infantilising union members while we infantilise ourselves and veer wildly between panic and complacency in relation to our future relevance.

This philosophy was, and where it remains, is essentially an ideology of managed decline in a deep seated culture of blame. It prevailed during many of the battles described in this book and at the moment Mark Serwotka finally became General Secretary of PCS. But the hard truth is that the evidence shows its dominance co-incided with sustained decline in union membership and power.

In these years PCS made a major and positive contribution to an industrial debate many unions have been ducking but has now presented itself starkly – how best to build our unions while gaining real impact our members can feel in their pockets in an environment of collapsing national bargaining and atomised workplaces. Debates rage over how best to rebuild collective bargaining: bottom up and inside out through parallel local and national bargaining with co-ordinated disaggregated ballots for action on the one hand - or through top down pay review bodies and sectoral mechanisms.

PCS was ahead of the curve in this regard for 20 years while it navigated the pitfalls of performative militancy and the temptation to build mass litigation over lay activism. PCS were among the first to work out the difference between democratic compromise in dispute rooted in the balance of forces – and concession bargaining, characterised by the phrase coined in the 2011 pensions dispute: “unions wandering the battlefield looking for someone to surrender to”

So the circumstances may be unique – and every union can claim that – but the battle of ideas between opposing philosophies is common and the PCS experience that John presents and analyses represents a significant milestone in this struggle for our unions future.

A core question the book poses is the problems that occur where unions seek technocratic organisational solutions to political challenges, solutions sometimes set out in detail in modern How to Organise text books by our movements gurus.

A fair critique but I would also argue that seeking political solutions to our current organisational problems – for example the hollowed out and eroded “Whitley” style collective organising structures across public services – also fails by ceding our future to the whims of external actors. The truth that the book embraces is that this narrative presents a false dichotomy and a false choice.

Successful union building requires both but I would hold that the evidence of 40 years demonstrates ably that a political approach to union building on its own will not throw up organisational solutions at any pace - but conversely, an organising approach will often throw up political questions as workers engage in their own struggle for justice.

Finally the book sets out an important lesson – winning the occasional conflict and battle of ideas between these two philosophies in a union is not enough. Gains must be consolidated and made the new normal if the philosophy of managed decline is not to re-assert itself as the default. This has certainly to be seen in some places

The book predicts that this conflict of ideas will deepen and strengthen within unions and the labour movement in the years to come. The impacts of the new “warfare not welfare” economy driven by the continued expansion of financialisaton and protectionism across the globe can be expected to drive attacks on workers standard of living at the level of the workplace, often through permanent contracting out cheered on by the emerging new populist right

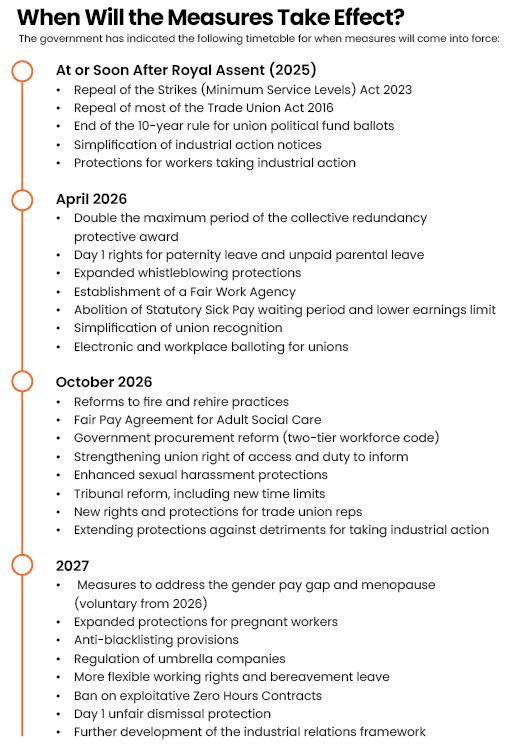

Working people want to join and organise unions as much now as they ever did. With the perspective developed through these struggles within PCS, and potentially some technical assistance from the proposed new Employment Rights Bill, our unions can choose to be ready to harness this energy by adopting a winning formula. Making our future more about choice than chance.

As the book asks: Which side are you on?

Comments